MOVIE REVIEWS |

INTERVIEWS |

YOUTUBE |

NEWS

|

EDITORIALS | EVENTS |

AUDIO |

ESSAYS |

ARCHIVES |

CONTACT

|

PHOTOS |

COMING SOON|

EXAMINER.COM FILM ARTICLES

||HOME

Thursday, May 3, 2012

IN MOVIE THEATERS THIS SUMMER

Confronting Yourself On The Big Screen And Exiting The Theater For Relief: Why Audiences

Flee "Compliance"

Dreama Walker as Becky, the tortured center of the troubling, divisive and

excellent "Compliance".

Magnolia Pictures

by

Omar P.L. Moore/PopcornReel.com

FOLLOW

FOLLOW

Thursday, May 3,

2012

They aren't fainting in the aisles or throwing up in the theater like

they did 40 years ago during "The Exorcist", or screaming with fright at "Alien"

just before the 1980s. These days, at film festivals in Park City, Austin,

San Francisco and elsewhere audiences are squirming and shifting in their seats, writhing and

gasping in shock and astonishment at the commands and incidents observed in

Craig Zobel's psychodrama "Compliance", a film that has alarmed, ruffled feathers,

offended sensibilities and deeply divided audiences.

"Compliance" is Mr. Zobel's second film (his first was "Great World Of Sound" in

2007.) Based on a true story at a McDonald's restaurant in Kentucky in

2004 (as well as built on at least 70 other incidents over a ten-year stretch

prior to that year), "Compliance" finds 19-year-old Becky (Dreama Walker), an

employee at the fictional ChickWich fast-food restaurant in Ohio accused by a voice over the

telephone -- a police officer (a great performance by a creepy Pat Healy) -- who says he has videotape evidence

that Becky has stolen money from a customer at the restaurant. Becky is adamant.

She's never stolen a thing in her life, she declares.

Becky's boss Sandra (Ann Dowd) is told by the voice -- an Officer Daniels -- that

she should search and detain Becky until the police arrive. She does.

From there things spiral disturbingly out of control. The audience is

held hostage to one cringing, nerve-wracking and horrific episode after another. No character

in the film calls the

police during Becky's ordeal even though a few declare that they won't do what

the voice on the phone tells them to.

Mr. Zobel's film uses the Milgram experiments of the 1960s as a distressing

theme. Those experiments were a series of electric shocks -- faked -- with

actors as victims pretending to be shocked -- after an administrator in another

room commanded a subject to increase the voltage on the victim if they answered

a question incorrectly. The shocks increased by 15-volts after each wrong

answer. When subjects grew skeptical of what they were doing to the

victims (many of whom claimed to have a heart condition), the administrator

would tell subjects to continue. Even after being told the shocks wouldn't

cause permanent damage despite "intense pain" --

subjects could hear the screams from an adjacent room -- the subjects continued the shocks at the behest of the

administrator, who stressed the importance of keeping the experiment going.

Shocks would routinely be increased in 15-volt increments from 15 volts all the

way up to 450 volts. Subjects were convinced that the victims were being

hurt. Sixty to

seventy percent of the time the subjects continued giving shocks to the victims

anyway. The subjects were everyday people, summoned to New Haven,

Connecticut as part of Yale professor Stanley Milgram's experiments.

Like the Milgram experiments "Compliance" highlights the grotesque things

ordinary people do in questionable or extraordinary circumstances, turning them

into instruments of monstrous, irrational behavior in spite of their better

angels. Sandra and her cohorts

know what they are doing to Becky is wrong but continue anyway, especially when told to

by a voice they consider an authority figure. The figurative alarm bell

named "why?"

occasionally rings out like a hypnotized but futile utterance, one spoken in

a trance-like way by several characters in response to Officer Daniels'

grotesque and unsettling requests.

"Why?" may be the only thread of resistance or opposition to the creepy phone

voice that these characters have left. "Why?" may be the only word that

prevents these human beings from becoming the very darkness or horror they seek

to escape. Becky, the film's most anguished victim, is compliant in

her own horrifying ordeal to an extent but with her exception "Compliance" shows

its players as both victims and criminals. The horrors that lurk within

these characters have always been there; it simply takes a shrewd, manipulative

agent like Officer Daniels or an off-guard, split-second to unearth them within

any one of us.

Us.

The audience that watches "Compliance" -- us -- is the biggest villain

of all.

One of the most popular responses -- by almost every audience member I spoke to

following the second S.F. Int'l Film Festival screening of "Compliance" -- was,

"I would never do something so stupid," or, "I couldn't believe how stupid those

people were." That common post-"Compliance" audience response may be a

visceral one but it may also be one uttered as a defense mechanism or a

distancing technique or as a buffer against their own very uncomfortable

reaction to what they have just seen. The hindsight, higher ground

response or "holier than thou" moral mountaintop declaration -- a way of

separating oneself from a film that forces the audience to participate in its

ghastly, invasive events particularly because of how it is constructed and shot

-- is the last line of defense for the audience, just as the word "why?" is the

last bastion for some of the characters in the film.

Dreama Walker as Becky,

an employee at the fictional fast-food restaurant ChickWich in "Compliance".

Magnolia Pictures

In both cases the line between the characters and the audience is inseparable

and the "why?" response and the "those people are so stupid!" response serve as

justified barriers or defense mechanisms against participating in bad behavior.

But do those responses do enough to rescue Becky?

That "Compliance" is inspired by or based on a true story is a horror unto itself but had it not been

the film would remain very convincing and plausible given aspects of everyday

human behavior familiar to all of us. We have all had moments of weakness

or lapses in judgment. We readily condemn these lapses in the political and

celebrity worlds. "Compliance" does not condemn them. The

film presents them without being sympathetic or indicting.

The audience watching "Compliance" however, is the most unforgiving of all.

So the overarching question is: why is it that a sizable number in any given

audience walk out on "Compliance" (which

opens in theaters in select U.S. cities on August 17)? Undoubtedly some

of the film's events are uncomfortable -- notably the matter-of-fact way it

shows

rational everyday people quickly and blindly assume authority simply because authority figures

confer it upon them or say that

it's okay to deputize oneself, even when those figures aren't physically present or even

seen. "You won't be responsible," Officer Daniels tells Sandra over the

phone in one scene. "I'll take the heat on this," he adds. Those spoken

lines illustrate a truism in human behavior: that if people think they can get

away with something that is bad, illegal or immoral, they will do that very

thing.

It is this real and disturbing everyday truth about human beings that "Compliance"

embraces and confronts head on, hurling it in the face of its presumably

escapist audience. In short, with "Compliance" and all of its economic,

class and generational tensions we

are shown something uncomfortable and inseparable from ourselves on the big

screen. There's no moralizing character in "Compliance" who jumps to

Becky's rescue in Act

Two-and-a-half or Act Three to say that what is happening to her is not only wrong

but criminal. No one hangs up the telephone and shuttles Becky, who has been stripped of her

clothes, out of the restaurant's backroom and safely home.

This is what the audience may well be most unsettled by, yet it might be safe to say

that some of those very audience members who exit the theater incensed and

troubled have in their own

daily lives observed things they knew were wrong yet failed to speak up or

affirmatively do something to prevent or address them. We've all been in

such situations.

So is it audience guilt, discomfort, something in their

own personal history or all of these that facilitate a hasty exit for some?

How many of us for example, have stayed quiet when a work colleague utters a

racist or sexist comment on the job, even though there are workplace handbooks

and state and federal laws in place specifically forbidding and not tolerating

such comments and behavior?

We escape the theater to seek refuge from a very uncomfortable truth about

ourselves. Some in the audience leave "Compliance" to escape from the

helplessness. Worse yet, the audience is miles ahead of the characters in

terms of what they know.

The only action for the audience is to either leave or stay.

There is an authentic psychological phenomenon called "diffusion of

responsibility", wherein people collectively rationalize a lack of urgency or

need to take responsibility for actions. Studies have shown that the lack

of accountability grows disturbingly as the group of people who observe a bad or

horrific act grows. The assumption is that someone else in the group will

take responsibility and do something. There's a "safety in numbers"

principle, or hiding place for people within a group as it gets larger. If

ten people witness a crime at work or on a street, the thinking is that there's

less of an incentive to be proactive to thwart it or take other action to bring

about its end, since

there's an implicit belief that someone else will. (It's like a fly ball in

baseball that two outfielders each think the other will catch but instead the

ball drops between them.)

When one is alone however, "diffusion of responsibility" says that people are

much more likely to act. (In the 1960s Darley and Latané established that

one's likelihood of action when responding to an emergency depended solely upon

how many were present. The likelihood of action grew with fewer people

around but diminished when more were present.)

Similarly, Darley and Latané found that when one person took action in a group,

others would be more likely to follow their lead, having been shown that it is

okay or safe to do so by the pioneering actor.

Ann Dowd as

Sandra, the manager of ChickWich restaurant in Craig Zobel's drama "Compliance".

Magnolia Pictures

Every day the human impulse to act or not act is tested.

How many of us have been shocked or literally frozen when hearing racist,

religious, sexist or other offensive jokes at work or from friends? (Do

you laugh with them, laugh uncomfortably or challenge them?) "Compliance"

covers that deep-freeze trance moment, extending it from an ephemeral twitch of

frailty, human ugliness or an unguarded second into a protracted, guilt-ridden 90

minutes.

There's an especially powerful cinematic moment where

cinematographer Adam Stone has close-ups of the eyes of several characters,

enhanced by Heather McIntosh's eerie, smart violin score. The quick,

succession of shots is a

moment of unspoken recognition of, checking in with, and an identification with the audience: we

all are capable of doing unthinkable and compliant things, especially when

trusted authority figures tell us it is okay to do so.

American tort law, administered by authoritative bodies, namely courts,

encourages and protects people from acting when seeing a stranger, in peril.

You can literally watch someone (a baby or one of any age) die before your very

eyes without having to save them, and not suffer criminal consequences as a

result of that failure. This is true even if you could save someone but

choose not to, because, say, you didn't want to get your clothes or new suit wet

by jumping into a water to save a drowning child's life. In most every

state in the United States, failure to act will not result in any criminal

charges in these specific examples.

Take, for example, the stabbing death of Kitty Genovese in Queens, New York in

1964. Ms. Genovese was literally killed in front of her neighbors on

estate grounds at night. Her death was seen by an estimated 70 people* who

watched from their windows. None of them shouted out to halt the

assailant's attack or telephoned the police, even as their neighbor screamed for her

life. They simply froze, watching like riveted, titillated, terrified spectators,

in much the way that automatic nagging curiosity within us compels us to slow down on a freeway

to look at

the sight of a nasty car accident. Is it that we want to see a body?

Blood? Is it that we can't look away because we want to see something awful?

Is that a subconscious desire in us as humans? The answer would have to be

yes.

The "Compliance" audience -- specifically those that walk out of the film are

wracked with guilt -- they could be akin to the same audience of spectators who

watched Kitty Genovese get stabbed to death. And how about those who

stay and watch the film? Even more so.

When some audience members walk out of "Compliance" it is their own form of

protest -- not necessarily against Mr. Zobel -- a nice guy who caught something

close to hell from some at the cold and snowy Sundance Film Festival after the

film's world premiere there in January. The protest is likely against his

anger-inducing characters, who seemingly know better and are actually more

intelligent than their undereducated trappings -- misspelled words like "employess"

are seen on a whiteboard in the restaurant's backroom --

might suggest.

It would be a grave mistake to say, as many who have seen the film so far have

said, that the people on the big

screen in "Compliance" are "stupid" people.

In real life people in large numbers initially supported

a war in Iraq that was clearly unjustified at the time, and in an absence of

weapons of mass destruction. Millions of Iraqis died as a result. In

reality, a large number of Americans believed Saddam Hussein was behind the

attacks on September 11, 2001, even when it was clear he was not, and even when

then-President George W. Bush said that "we have no evidence that Saddam Hussein

was behind the September the eleventh." And that was said after

the war in Iraq had begun.

How about the Orson Welles "War Of The Worlds" radio broadcast in 1938 which

prompted many people in America to believe that Martians had declared war and

were going to invade New Jersey?

It all appears silly in hindsight but the point is this:

We can all be fooled. We can all be gullible. At any given moment.

Stupidity has nothing really at all to do with it.

Even more scary: in World War Two many so-called "good Germans" stood by while

millions of innocent Jewish men, women and children were executed. U.S.

presidents held enslaved Africans in their homes and estates while talking about

freedom for America. Richard Nixon once talked of "the silent

majority", a majority that for this writer's money is often more homogenous, malleable

and terrifying than the brave few who challenge the status quo.

In reference to the real-life McDonalds' incident on which "Compliance" is

based, on one Internet message board someone says, "no law enforcement official

or police officer would ever ask someone to take all their clothes off!"

The poster of that comment obviously hadn't read these news stories (a,

b,

c) or seen this

video. The video of the actual events

"Compliance" depicts is far more disturbing than anything shown in the film.

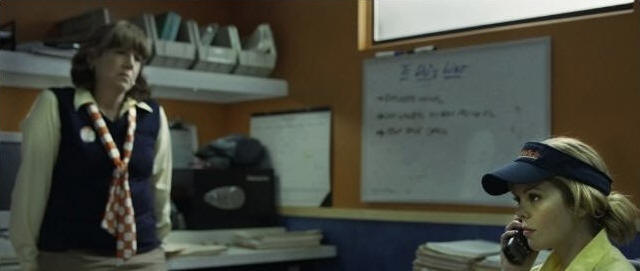

Dreama Walker

as Becky (on phone), under the watchful eye of Sandra (Ann Dowd) in "Compliance".

Magnolia Pictures

With "Compliance" Mr. Zobel hits a nerve and approaches the line of chronicling

a spectacle of

victimhood but doesn't cross it. Mr. Zobel's camera does less to celebrate

victimhood or voyeurism than it does the perilous descent into groupthink and the

rational becoming the irrational in the chilling blink of an eye. People are

prodded on a psychological level in "Compliance" the way they were by Yale

professor Stanley Milgram. Mr. Zobel tries to get the audience to watch

the uglier aspects of human nature but doesn't exploit. Cameras move away

at key moments and audiences, faced with the horrors unspooling before them,

do so too.

The audience's only recourse -- in that sublime, plush-seated environment designed for escapist visions

-- is

to escape. To flee. In the film's initial screening at the San Francisco

International Film Festival last month

30 people walked out. In the

second and final screening of "Compliance" at the Festival, nine exited,

including a lady in her sixties sitting next to me who said, "I just can't watch any more of this."

"Compliance" is an instructive look at socio-psychology, and a breakdown in

common sense. The camera captures Sandra and other characters in

imbalanced framing, kooky Dutch angles and floating headspace as if tilted on a

very slowly-swinging pendulum. Sandra is ingratiated with and appraised by

Officer Daniels, who talks her up, charms her, wins her trust and encourages her in

ways that Stockholm Syndrome victims end up lauding their captors even after

they've been horrifically mistreated. Patty Hearst is one very famous

example.

Thus far "Compliance" is the year's best film, and whenever a film has the power

to shock, engage and move you in profound and smart ways without being

gratuitous it has done its job well. "Compliance" tests the audience's

own complicity in the film's events with its own reaction to them.

The dilemma becomes this: If

people walk out are they abandoning Becky? If they stay are they

symbolically complicit in the awful events Becky endures? As great art

"Compliance" is a Rorschach test. It's also a horror film without

bloodshed. All the horror is psychological, and very authentic. This

is what troubles audiences. There are no theatrical conceits or

recognizable movie devices that actively or sufficiently divorce the audience

from Becky's agony, which is hours and hours long (and was in real life),

condensed into about 40 minutes.

Sandra says that she is only doing what is right but is it because she really

believes it or because a police officer tells her to? By the time any

proper reflection on that specific question is entertained, it is far too late.

The wheels are already set in motion. Experiments have shown that the

reactions of Sandra and others in "Compliance" of non-action, peer response and

compulsion and such other practices, are common, very internal, part and parcel of the

human make-up and everyday response and inaction.

The good news is there are people who break free of this troubling inaction.

People on plane flights have stood up to defend themselves and others when a

passenger gets out of control. Others have saved lives. Anonymous

persons and famous ones (Ryan

Gosling, Tom Cruise for example) could have chosen to watch

as people died but instead they ended up saving lives.

Would they have felt less compelled to do so if part of a group of more than

three was with them? Studies tend to signal yes.

"Compliance" is an opportunity to watch human behavior -- and not so

much film character behavior -- up close and personal. There's no filter.

Nothing separates the audience from these characters and their decisions except

a screen and hindsight. These characters truly are us. We are

looking into a mirror when we see "Compliance", and what we see isn't pretty.

"Compliance" opens in select U.S. cities on August 17, and expands to

additional cities thereafter.

At Sundance 2012: Craig Zobel (left), the director of "Compliance", with actor

Pat Healy, who plays

Officer Daniels in the film.

Larry Busacca/Getty Images

*Note on Kitty Genovese:

several readers have rightly pointed out that indeed some neighbors had in fact

contacted police. Many writers at the time "sensationalized" the events

surrounding Ms. Genovese's murder. No one knows with certitude all of the

circumstances surrounding her murder. I have read accounts that said an

estimated 70 people saw her murder. Others have said 38. Some helped

but the few who did try turned out to help in vain, as police arrived quickly

but a little too late. The sad, bottom line in the Kitty Genovese case is

that no matter the number of people who were inactive while witnessing the

horrific events, a woman was raped and murdered.

COPYRIGHT 2012. POPCORNREEL.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.  FOLLOW

FOLLOW

MOVIE REVIEWS |

INTERVIEWS |

YOUTUBE |

NEWS

|

EDITORIALS | EVENTS |

AUDIO |

ESSAYS |

ARCHIVES |

CONTACT

| PHOTOS |

COMING SOON|

EXAMINER.COM FILM ARTICLES

||HOME

FOLLOW

TWEET

FOLLOW

TWEET

FOLLOW

FOLLOW