MOVIE REVIEWS |

INTERVIEWS |

YOUTUBE |

NEWS

|

EDITORIALS | EVENTS |

AUDIO |

ESSAYS |

ARCHIVES |

CONTACT

|

PHOTOS |

COMING SOON|

EXAMINER.COM FILM ARTICLES

||HOME

Friday, June 27, 2014

TWENTY-FIVE YEARS LATER

"Do The Right Thing", Then And Right Now

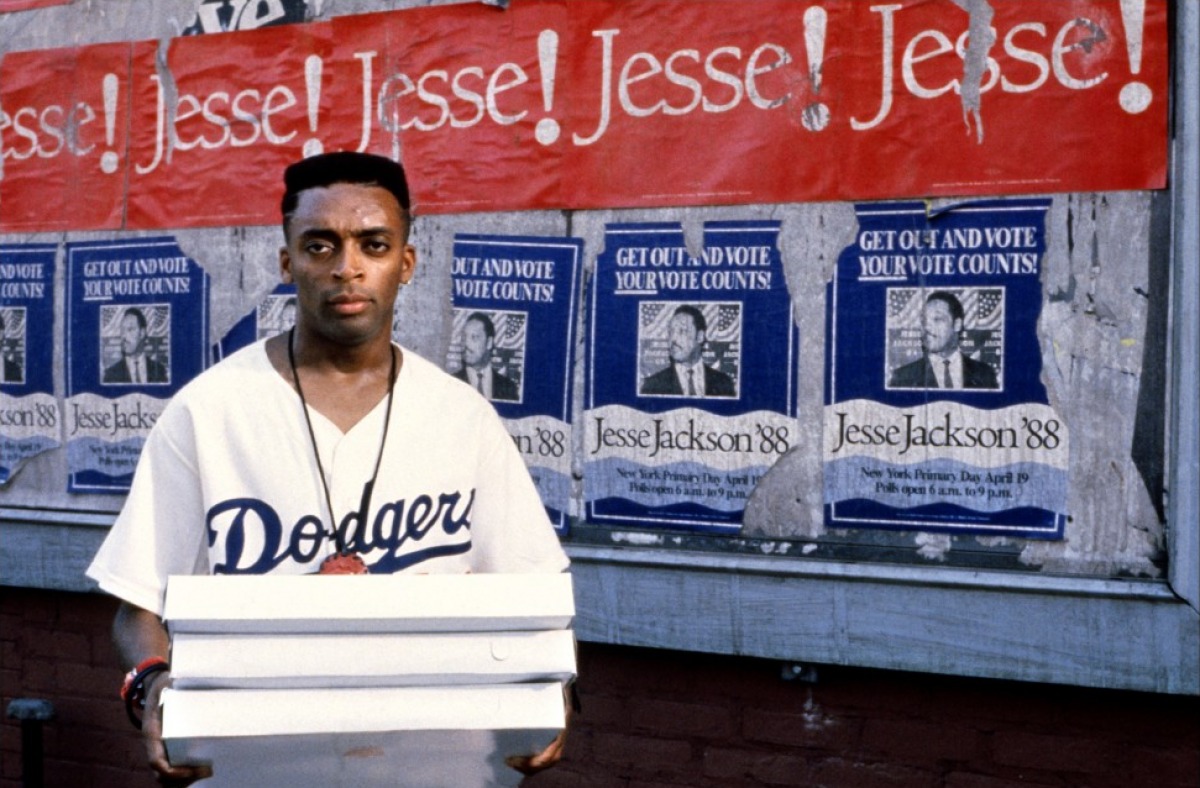

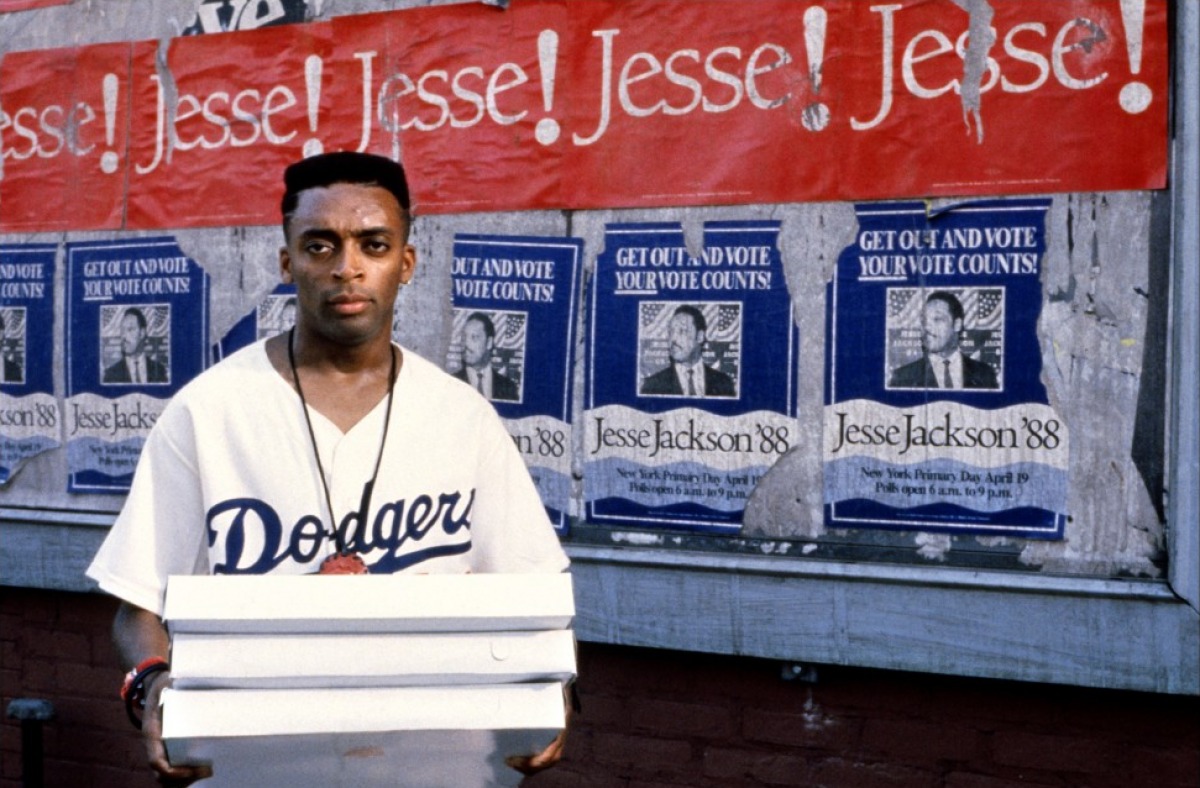

Spike Lee as

Mookie, a pivotal character in the

director's legendary

"Do The Right Thing", which turns 25 on June 30.

Universal

by

Omar P.L. Moore/PopcornReel.com

FOLLOW

FOLLOW

Friday,

June 27,

2014

June 30, 1989. That was the date that Spike Lee gave the world "Do The

Right Thing". I'm not sure the world has been quite the same since.

That summer in 1989 -- what a hot, feverish New York City sweat bath it was! --

I saw "Do The Right Thing" on the big screen in the very early morning hours of

Sunday, July 2, the last "Saturday" night show, at forty minutes past midnight,

at the-then East 59th Street Cineplex Odeon in Manhattan. I had waited

three hours in "Star Wars"-length lines to see it. The Odeon theater was

packed. I sat at the very back. The audience was racially mixed and

age-diverse.

"Do The Right Thing" was an intense, vivid experience. Every frame was

vibrant. Every shot had life. Nuance. Humanity. Every

colorful, eye-popping image spoke volumes. I felt this film in

unmistakable ways: in my heart and soul. The final confrontation in Sal's

Famous Pizzeria and the death of Radio Raheem I replayed over and over in my

mind. I saw "Do The Right Thing" again a week later. Then again

about a week or two after that. The feelings I had remained the same each

time. They still do.

Mr. Lee's third feature remains the zeitgeist of New York City and America in

terms of race relations and racial justice. In racial, sociopolitical and

economic terms "Do The Right Thing" evoked what was happening in America in 1989

and now. The film's atmosphere and setting was Brooklyn, specifically

"Bed-Stuy Do-Or-Die". In 1989 the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn

was predominantly black. In the film, characters debated gentrification

passionately, as if they knew what the future held. In 2014

Bedford-Stuyvesant is diverse, populated by many whites, some of whom would

likely have seen it as a no-go zone in the early 1990s.

Mr.

Lee himself talked about gentrification and culture and its affect on

New York and other U.S. cities earlier this year.

At the time "Do The Right Thing" was shot in the summer of 1988 revelations by

Tawana Brawley had unfolded. Two years earlier Michael Griffith was

murdered by a white mob in Howard Beach, Queens. Both of these events, as

well as other New York City racial flashpoints and injustices, were

incorporated, either purposefully or accidentally, into "Do The Right Thing".

An encounter between a Korean grocer and two black characters in one climactic

scene ended in edgy conciliation in the 1989 film. Less than a year later

about two miles away in the same borough of Brooklyn in real life, a black woman

was assaulted inside a Korean grocery, prompting a nearly year-long boycott.

In March 1991, a sixteen-year-old black girl, Latasha Harlins, was shot dead by

a Korean grocer in Los Angeles. That same month Rodney King had been

brutalized by L.A. cops for all the world to see. Neither event resulted

in convictions.

As its theatrical release arrived a few white film critics like Joe Klein of New

York Magazine, among others, declared that "Do The Right Thing" would cause

riots by blacks in New York and across the country, essentially saying that

white people would be better off staying at home and avoiding theaters. It

was racist fear-mongering at best. Such ignorant sentiments arguably kept

a sizable number of white moviegoers at home. Mr. Lee often laments that a

large number of whites have since accosted him, saying they first saw "Do The

Right Thing" on video, not on the big screen.

As for those film critics' predictions of blacks rioting, the only thing that

happened that summer following the release of "Do The Right Thing" in the U.S.

was the murder by several whites of Yusef Hawkins, a black teenager who had

merely answered an ad for a used car in the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn.

I had marched through Bensonhurst a few months after "Do The Right Thing" was

released. Police were the only line of safety between a few hundred

marchers and a full-scale white riot. It was a scary, ugly sight.

The climate of racial hatred had been so vicious on that autumnal Saturday in

1989 that it felt like 1964 Mississippi. Throngs of men, women and

children, young and old people -- just like those who attended Klan lynchings of

blacks -- lined the sidewalks on either side of us, five or six deep, screaming

racist invective, holding up watermelons and basketballs, mooning us and

spitting at us.

Today Bensonhurst, like Bedford-Stuyvesant, is far more diverse.

The art-imitates-life aspect of "Do The Right Thing" was astounding.

Inseparable. The fictional, authentic characters uttered the realities of

everyday life. When one of the characters shouts of Radio Raheem, "he died

because he had a radio!", you could easily think of Jordan Davis, who was killed

in 2012 by a white man who said the hip-hop music coming from the car Mr. Davis

sat in was loud.

You may think of Trayvon Martin, killed in a not so dissimilar manner from Mr.

Hawkins. Just minding his own business. Sal Frangione and Michael

Dunn could be the same person. Both had a distaste for blacks. Sal

and Donald Sterling could be twins: business owners who liked operating in and

benefitting from the attributes and financial success blacks brought them while

secretly or overtly despising blacks at the very same time.

The political ramifications were also clear in "Do The Right Thing". The

motifs burned bright. Mookie wore Jackie Robinson's Brooklyn Dodgers

jersey, a symbol for a man whose legacy was activism and justice-seeking.

Ossie Davis's Da Mayor character resembled then-New York City mayoral candidate

David Dinkins. The film's "Dump Koch" graffiti was evident. Mr. Lee

said he hoped his film would help oust Ed Koch, who had accentuated the climate

of racial tension and division in New York throughout his decade-plus long

tenure as the city's mayor, from office. Mr. Lee's wish was granted.

Mr. Koch lost to eventual mayor Mr. Dinkins in the Democratic primary three

months after "Do The Right Thing" was released.

Posters of Jesse Jackson's 1988 presidential run were a backdrop in Mr. Lee's

film, and now, over 25 years later, an often pilloried and disrespected

President Obama sits in the very office Mr. Jackson ran for. Mr. Jackson

was a disciple and close friend of Dr. Martin Luther King, whose quote, along

with Malcolm X's, form a coda to "Do The Right Thing". Both quotes, on the

impact of violence and its effects, speak to much the same points and are closer

in commonality than some may wish to think.

"Do The Right Thing" is a series of minor and major incursions and invasions of

space, territory and assumption. Each of these elements is played out then

countered like moves on a life-sized chessboard. Calculation, percolation,

escalation. The mechanics of the film's characters, predicaments, social,

cultural, historical and racial realities were emblazoned throughout in ways

large and small. In all that the memorable characters of "Do The Right

Thing" said, felt and did, their naked honesty pierced the screen.

I maintain that Spike Lee's film represented one of the most honest and genuine

conversation starters about race and racism in America. In that summer of

1989 I had discussions about the director's film with my white work

colleagues. We viewed "Do The Right Thing" very differently. Two

colleagues I spoke to were worried about Sal's pizzeria being destroyed. I

was concerned about Radio Raheem being killed for no reason at all.

There's "Imitation Of Life" and numerous other films, but "Do The Right Thing"

was one of the signature films about race, class and conscience. It

confronts you and compels a reaction. Complex, even-handed and nuanced,

the film is an open-ended question rather than an attempt at an answer to the

deep, still-very real (and worsening) problems of institutional racism, and the

casual racism within those who believe they aren't racist.

"Do The Right Thing" was the groundbreaker, in lots of ways.

One of the questions I still ask myself and others 25 years later, is, why

didn't Sal simply call the police? As he smashes Radio Raheem's stereo box

to pieces with his baseball bat, a pay telephone, which we have seen used in the

film at least once before, is less than two feet from him. The police had

visited Sal's Famous Pizzeria just moments before. Why didn't he use it?

"Do The Right Thing" has its 25th anniversary on Monday, June 30.

COPYRIGHT 2014. POPCORNREEL.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.  FOLLOW

FOLLOW

MOVIE REVIEWS |

INTERVIEWS |

YOUTUBE |

NEWS

|

EDITORIALS | EVENTS |

AUDIO |

ESSAYS |

ARCHIVES |

CONTACT

| PHOTOS |

COMING SOON|

EXAMINER.COM FILM ARTICLES

||HOME

FOLLOW

TWEET

FOLLOW

TWEET FOLLOW

FOLLOW